Urban renewal remains a rhetorical and contextual constant in today’s discussions about planning and policy, even though 60 years have passed since the apex of the idea’s power in American life. The term is invoked by a wide variety of people to make a wide variety of points carrying a wide variety of intellectual consistency and honesty; indeed, at times it seems near-ubiquitous in urbanist or planning discourse. Perhaps unsurprisingly, talk about urban renewal and its legacy often focuses on the Robert Moses vs. Jane Jacobs paradigm and the lessons about community control and out-of-control bureaucracy. With perhaps somewhat less frequency, renewal is used as a weapon in the never-ending online wars about whether capitalism or socialism is worse (it is perhaps testament to how uniquely terrible an idea urban renewal was that it allows both sides of that debate to use it with a truly straight face). And of course, discussion of renewal often veers off in a hyperbolic and/or totally non-factual direction. This, then, represents my attempt to reset the urban renewal discourse a little and re-focus it on what renewal was really, consistently about: cars and autocentricity.

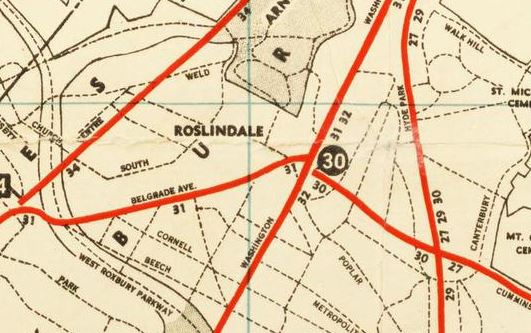

It’s worth taking a moment to define our terms. Strictly applied, the term “urban renewal” originated with the Housing Act of 1954, but the concept of “slum clearance” became popular with Title I of the Housing Act of 1949. In general discourse, it has become customary–and I think useful–to bundle these federal housing programs with the mass demolition of urban neighborhoods for freeways, most associated with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. While these federal programs mostly wound down in the face of opposition and lack of success by the 1970s, in some cities the robust powers granted to government to facilitate them still exist, even if they now receive less frequent usage. I use the term to refer to the entire assemblage of programs at all levels of government that pushed hard for the destruction and redevelopment of neighborhoods through a philosophy of built-environment determinism and a conception of determinedly auto-centric mobility.

Many on the left (but not just those on the left!) understand renewal as a joint conspiracy of capital and government. An example: this quotation from former Cleveland planning director Norman Krumholz, the originator of the “equity” or “advocacy” school of planning, in this NextCity article about Boston’s recent fights over whether to extend the city’s renewal powers:

“You know the story of urban renewal: low-income people driven away from choice locations that developers selected for redevelopment.”

And although there’s certainly truth in the idea that capital and corporations drove renewal , this analysis is at best incomplete. For one thing, the massive reshaping of cities to accommodate megablock development and autocentricity was a worldwide phenomenon at the time, hardly limited to capitalist economies (indeed, if anything it was notoriously worse in socialist or Communist countries).

https://twitter.com/mtsw/status/897247248249225216

https://twitter.com/mtsw/status/897247338040885252

The narrative that renewal happened because “developers” or “capital” demanded it exists in some tension with the idea that it was the fault of authoritarian planners and bureaucrats. It also happens to elide the fact that the physical effects of renewal were popular with large swaths of the growing white upper and middle classes in the postwar period; indeed, of all people Robert Moses saw himself as responding to the demands and interests of this powerful class (while of course also being an egomaniac). Douglas Rae’s City: Urbanism and its End gives a glimpse into this process in the city that took more federal urban renewal money per capita than any other; while New Haven’s business and institutional communities provided substantial support to urban renewal, renewal was also a downright popular policy with the suburbanizing middle classes (which benefited from easy auto access to downtown) and with urban liberals (who saw it as a positive government intervention). I grew up in New Haven in a community that frequently discussed the trauma of urban renewal–but many of the same people who mourned the loss of the old Jewish Oak Street neighborhood are perfectly capable of complaining in the same breath about the (perceived) difficulty of parking downtown. I’m sure many people who think critically about land use and transportation issues have similar stories: it’s a useful reminder that at least some of the tenets of urban renewal remain popular to this day.

Reminding the public of the centrality of auto dependency to renewal has become necessary in large part because of the emergence of a particular dynamic where certain people (in good faith or bad) claim the mantle of fighting urban renewal specifically to preserve faux-populist autocentric practices in planning. Their narrative typically adopts aspects of the leftist story about renewal, whereby the core legacy of the fundamental trauma associated with renewal is the lesson that community control of planning processes is an absolute obligation and an inherently positive way of doing policy. The result is an inherently contradictory, and often toxic, dynamic that instead of striving to discuss the potential conflicts in the legacy of urban renewal instead clouds history and obstructs any attempts to undo renewal’s physical legacy in the present day.

One genre of attempts to twist renewal’s admittedly highly undemocratic processual legacy into preserving its physical legacy is the preservation of open space at the expense of the potential to restore the dense development that in many northeastern cities existed before the era of renewal. One of my favorite hangouts in Albany was Hudson-Jay Park, a small green space carved out of the junction of the dense brownstones of Center Square and the Modernist marble wall of the Empire State Plaza, and a legacy of land cleared for a never-built planned freeway tunnel entrance.

Hudson-Jay Park in Albany, looking east toward the Empire State Plaza. Author’s photo.

Or take the example of Meriden, Connecticut, which I wrote about in 2014. In the core of downtown, right across the street from the railroad station, a giant, autocentric mall had torn down several square blocks of dense urban development decades ago. With the coming initiation of more frequent rail service on the Hartford Line, Meriden engaged in a generally positive community process designed to revitalize downtown with TOD….but instead of restoring dense development on the former mall site, built a giant transit-oriented park.

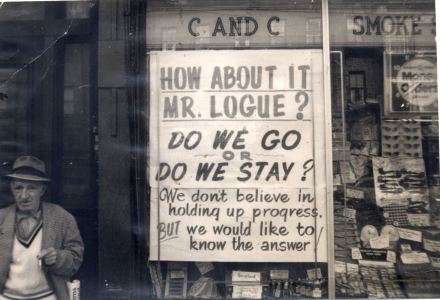

Meriden is, though, an economically depressed city where the demand side of the development equation is unclear and where community members may be less conscious of exactly how they’re handling the legacy of urban renewal, so let’s take a look at an example closer to my current home. Last year MassDOT sold off a number of small plots of land along the Southwest Corridor in Jamaica Plain (JP). The plots are a direct legacy of the era of urban renewal and freeway construction; the state had seized them decades earlier in order to build a freeway on what’s now, after a civic revolt, the Amtrak/MBTA line known as the Southwest Corridor. Since rail lines, even with an accompanying greenway, take up much less room than a freeway, the state was left with a number of leftover lots, some of them of irregular size or shape, but many of them potentially suited to restoration of the dense pattern of development that existed before the massive use of eminent domain and land clearance in the area. Since the construction of the Southwest Corridor, some of these lots have become open space or part of the greenway; others serve as community gardens. Indeed, one of the lots was taken off the auction block in order to formalize its use as a garden. An anonymous Twitter user took the time to argue with me, contending that my desire to see public land used for a purpose higher than community gardening was, in fact, insensitive to the memory of the struggle against urban renewal:

Similar thoughts appeared elsewhere during the discussion. I think it’s worth diving into that a little bit. In the mind of this Twitterer–and numerous other JPers–fighting urban renewal has nothing to do with restoring the dense development that characterized pre-renewal JP, or fighting autocentricity per se, but relates exclusively to honoring the wishes of the self-defined “community” that once fought renewal–and no one else. Fighting to preserve open space–open space that had not always been that way!–in an area truly rich in it when Boston is suffering from a housing crisis induced in large part by the era of urban renewal seems, in contextual reality, not only quite far from honoring the fight against renewal but indeed supportive of the very ideas that drove renewal in the first place. What better honors the JP that existed before renewal: a community garden or moving toward rebuilding, for example, the vibrant commercial area that once existed around what is now Green Street station on the Orange Line?

Jamaica Plain railroad station, on the current site of Green Street MBTA station, around 1910. Note the significant commercial and industrial development around the station. Source: By Unknown – Scanned postcard from eBay auction: “JAMAICA PLAIN MASSACHUSETTS MASS. RAILROAD DEPOT TRAIN STATION VINTAGE POSTCARD”, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45952810

Green Street station today, looking south from the corner of Green and Amory. Note removal of all commercial buildings (although there is one behind the camera) and empty lot at the southeast corner of Green and Amory; I’m told local residents have opposed new construction on this lot.

It’s worth thinking about the implications of an ideology (although it’s hardly theorized enough to be called that, the feeling seems common enough) of open space-as-antidote-to-renewal. I would, bluntly, posit that this ideology is in no way an antidote to renewal and in fact in many ways accepts and cements the Corbusian principles underlying the entire concept of urban renewal. It’s towers in the park, minus the towers, but with some (but not too many) handy restorable brownstones or triple-deckers.

This ideology of garden-as-preservation-from-renewal is, whether consciously in the minds of its proponents or not, inseparable from the same kinds of (mainly white) middle-class consumer desires that actually drove renewal as an ideology. In his highly original and significant The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn, Suleiman Osman lays out how 1960s South Brooklyn gentrifiers created narratives of saving their “middle ground” (that is, between Manhattan and suburbia) areas from the twin threats of Robert Moses-style Modernist renewal and the uncaring natives who were allowing the area to decline. These narratives, obviously, were self serving, and in them we can see the seeds of some of the more obnoxious aspects of gentrification today. But we see arguably the same logic at play in JP and elsewhere today, as some defend de-densifying the neighborhood and preventing the restoration of transit-oriented development as fighting renewal. Like Osman’s South Brooklyn gentrifiers, the people who fought fiercely for their neighborhood in the face of the assault of Corbusian, autocentric renewal deserve credit for preserving an ideology of urbanism of sorts in decades past–and critique when they end up doing the work of autocentrism.

Understanding the fetishization of open space in the wake of renewal as a middle-class consumer ideology largely invented by gentrifiers makes the second, and far more challenging, common genre of slightly-off references to urban renewal somewhat jarring. This is the tendency of leftist anti-gentrification activists and some within communities of color to refer to densification and transit-oriented development efforts as a variation on urban renewal. On the one hand, where community consultation is lacking–or even where it is done well, but displacement is accelerating because of strong market demand–it’s reasonable for fearful people to interpret pretty much any action policymakers take as not reflecting the wishes of the community and therefore bringing up the spectre of renewal (and in a situation with limited good options, policymakers should be ready to be accused of not being consultative enough no matter their choices). On the other hand, this accusation completely erases the aspects of urban renewal that had to do with autocentricity and the consumer desires of the white middle class for easy car access throughout the city and easily available parking–which is to say, most of the core of the renewal ideology.

A typical example is this from Erick Trickey’s reasonably good article on the Green Line light rail project connecting Minneapolis and St. Paul in Politico:

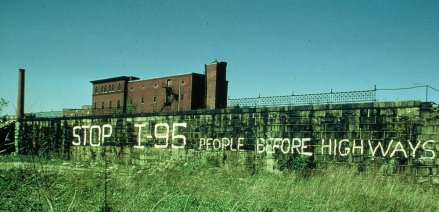

And many poorer communities along the route simply didn’t believe the Green Line would benefit them. They saw light rail as a threat that would disrupt their neighborhoods and bring gentrification—a sequel to the urban-renewal projects of the mid-20th-century that bulldozed poor communities for the sake of suburban commuters…Another reason for opposition—which surprised transit planners and city leaders—was the long memory of St. Paul’s older African-American residents, who’d been victimized by racist highway policy a half-century before. Rondo Avenue, the main business strip in St. Paul’s largest black neighborhood was bulldozed to make way for the I-94 freeway in 1960. That destruction of more than 600 black families’ homes and dozens of black businesses—a tragedy the federal government replicated in black neighborhoods across the country—ripped apart the city’s African-American middle-class economy, inflicting lasting damage to black families’ wealth and homeownership. (A play about Rondo, The Highwaymen, played this February at St. Paul’s History Theatre.) So for some black residents south of University Avenue, another transportation project in their neighborhood felt like war….Nathaniel Khaliq, who was president of the St. Paul NAACP at the time, lost his childhood home on Rondo Avenue to I-94. To avoid any repeat of the disruption the freeway had caused, he preferred an earlier proposal to place the train tracks down the center of I-94. When transit planners chose University Avenue as the route instead, the NAACP sued.

There’s a lot to unpack here. There should be no doubt that community concerns about displacement and racist policy were, as they often are in other cities, valid; while the vulnerability of poor people of color to displacement is a symptom not of transportation policy but of much larger structural forces in American life, it is in many ways felt most acutely in areas with new high-quality transit, given the overall scarcity of such systems in this country. But there’s no escaping the contradiction inherent in the rhetoric and suggestions here. Put simply, the way to protect the black community from a second wave of urban renewal was to replicate the physical planning practices of the original urban renewal programs. Putting rail transit in a freeway right-of-way was for decades, and in some places remains, a common practice, but it’s a really crappy idea that exposes passengers to pollution and minimizes walking access to stations–and cements (literally) the autocentricity of the built environment.

Damien Goodmon of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition provides a somewhat more hyperbolic example of this train of thought in last week’s post in response to Scott Wiener’s ambitious attempt to solve California’s housing crisis by taking the revolutionary step of … building housing. In response to the idea that dense development should accompany transit, Goodmon declares,

Not since the “Urban Renewal” projects of the 1960s (most appropriately characterized as “Negro removal” by James Baldwin) has something so radical and detrimental to the stability of urban communities of color in California been proposed.

Certainly, Wiener’s bill as proposed would markedly transform many California communities. But Goodmon’s attitude points to a tension in the concept of what’s “good for” disadvantaged communities. It is, in today’s immediate context, somewhat reasonable for communities of color and poorer communities to understand some transit projects and the project of restoring transit-centric urbanity as not being primarily “for” them. In many cities, transit lines generally run radially, connecting outlying neighborhoods to downtowns; as downtown employment has in many cities become increasingly white-collar, low-wage/low-skill employment has fled to the suburbs–often to areas impossible to serve well with transit because of terribly hostile land use. In polycentric Los Angeles, jobs and other trip attractions are spread widely across the metropolis, a development pattern that can be equally hard to serve with transit. Car usage, then, becomes an apparent necessity for low-wage workers, even as it represents a massive financial burden.

However, as I’ve written about New Haven, we should understand this dynamic as being a product only of today’s immediate context, not as inevitable but as a consequence of a series of autocentric policy choices beginning with the era of urban renewal and pushed over the course of decades by the car- and parking-obsessed white and white-collar classes. Thinking of restoring transit-centric development patterns as a follow-on to urban renewal, rather than a refutation of it, only makes sense if one cannot envision a future where disadvantaged people gaine equal access to the world of mobility by transit–a world that should logically be far more hospitable to them than the literally poisonous world of autocentrism. It is possible that if Scott Wiener’s SB 827 were to be enacted as written, it would lead to a traumatic change in specific black and Hispanic communities in LA (though smarter people than I have expressed doubts about that, expecting most new construction to occur on LA’s rich, NIMBY Westside). Yet it is virtually inevitable that in the long run life for the poor and vulnerable in California would be greatly improved by greater housing availability, more transit, and the restoration of the ability to live a life without car ownership, now effectively government-mandated in much of the state.

There’s a lesson there for policymakers, and it doesn’t consist exclusively of “consultative planning is the way to make up for urban renewal.” Rather, it’s that undoing the damage wrought by renewal is a long-term process that we must consistently center on strong principles relating to mobility, design, safety, and equality. Taking once more the example of New Haven, which has hollowed out its downtown for parking at the demand of white-collar professionals, only to see increasing numbers of jobs taken up not by city residents but by suburban commuters. It is those demands for parking, and those worries about the speed of traffic that lead to widening of streets, marginalization of transit, and increasing hostility to pedestrians, that represent the true core of the anti-humane and inegalitarian legacy of urban renewal.

To some extent, I think urban renewal discourse has become so toxic and counterproductive precisely because we find ourselves at a moment of transition and crisis. Urban renewal and freeways destroyed the spatial/economic logic of transportation and land use that had prevailed since the beginning of urbanity, a logic that values physical access and proximity. With the end of construction of new urban freeways (with some horrific exceptions) and growing congestion strangling suburban highways, that logic–one that rewards compactness and punishes spawliness–is reasserting itself rather strongly. It is, perhaps, a testament to the lasting autocentric effects of urban renewal that many people, including advocates from the very communities that have suffered most from renewal, are struggling so hard to adapt to the new/old reality.

Fighting autocentrism remains an uphill battle in the US. As I hope I have made clear here, despite the reassertion of basic spatial logic in recent decades, the principles of autocentricity, car mobility, and easy parking introduced by the era of urban renewal have proven extremely durable and remain in practice remarkably popular, no matter the consensus on Urbanist Twitter. It’s important to keep in mind, then, that those principles ultimately reflect a spatial, economic, and social ethic not of equality and egalitarianism, but of segregation and geographic injustice–an ethic that has done enormous damage to vulnerable communities across 60 years of car-centric American living. The lesson here is, to say the least, not to liberate vulnerable communities, or preserve “authentic” urban neighborhoods like JP, by cementing autocentricity, but to smash the wheel entirely, taking our inspiration from a renewed understanding of the core meaning of renewal–and from aspects of the neighborhoods and networks that existed before it, modified with the lessons we have learned about democracy, privilege, racism, and egalitarianism in the meantime. Onwards.