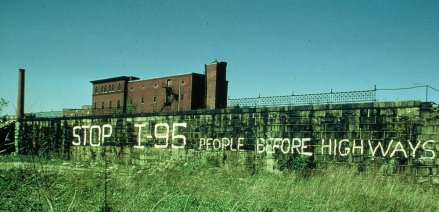

I finished reading two very different, but equally interesting and informative, recent urbanist-y books over Shabbat. The first is Akum Norder’s The History of Here, a fun and talented Albany writer’s look into the history of her family’s house, the people who have inhabited it, and the life of the neighborhood around it. The second is Karilyn Crockett’s People Before Highways, an ethnographic and historical look of the anti-freeway movement in the Boston area in the 1960s and ‘70s. Both books are worthy of a full-scale review that I may or may not be able to undertake at some point, but I wanted to pull out a common element that I think makes for an interesting, and very relevant, point of discussion: the question of how democratic planning should be, and how that should look.

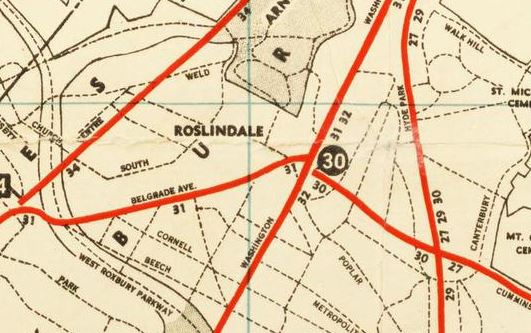

Let’s start with People Before Highways. Crockett’s work is essentially an ode to the grassroots anti-highway backlash that transformed transportation policy in Massachusetts and led to the end of freeway building inside the Route 128 beltway and the ability to “flex” federal transportation spending from highways to transit. Boston’s anti-freeway coalition was a broad–and varying at different times–group of institutions, scholars, “radical” planners like future Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation Fred Salvucci, and community members. The last element is perhaps the most interesting; participants ranged from tenant activists in public housing to Black Panthers to patricians in Brookline and Cambridge to people we would now identify as first-wave gentrifiers in the South End and my own neighborhood of Jamaica Plain. This coalition demanded not just an end to highway building, but also to the heavy-handed way in which the freeways had been planned, and significant amounts of land taken, with virtually no opportunity for public input. Crockett wastes no opportunity to remind the reader that the demands of the Boston anti-highway movement were not just specifically anti-highway, but processually radical and progressive in their insistence on the distribution of power.

Certainly, the righteousness of the Boston anti-highway, pro-public participation cause is not in dispute; it’s a difficult book to read for a professional planner. One thing that strikes me about Crockett’s work, though–and it’s a problem I’ve seen elsewhere in leftist planning thinking and writing–is that her narrative is shaped by a powerful nostalgia for the kind of grassroots planning and localist democracy that her subjects believed in, but doesn’t engage with some of the potential challenges of a highly democratic process. Indeed, some of the potential challenges with such a process show up even within her own research. In the sixth chapter of the book, Crockett profiles the planning process around the creation of the Southwest Corridor linear park, by all accounts pretty much a triumph of democratic planning that created a valuable community amenity and showpiece to this day. The cracks in the process of democratic planning, though, show through this account. Crockett shows how the South End community was able to demand that the Southwest Corridor trench through their area be roofed over to reduce noise, pollution, and vibration. This is, of course, not an unreasonable ask–but Crockett’s account makes it clear that the presence of educated, middle class people in the neighborhood, including some who we would clearly call gentrifiers today, was what got the deck built in that section, but not elsewhere in the Southwest Corridor. Why, one thinks today, is the trench not decked through Roxbury and Jamaica Plain? I lived a block from the trench for my first 10 months in Boston, and one can feel the vibrations and hear the roar from passing trains. A purely “democratic” planning process is already one that gives greater voice to those able to shout loudest–and Crockett’s account of the decking of the South End trench shows how this can lead to opportunities being available inequitably.

Crockett also narrates the process for planning the park that went on top of the South End trench, and if anything it reveals more of the cracks in the facade of democratic-planning-as-magical-cure. She writes:

By removing the railroad’s stone embankment and inserting decking along segments of each section of the Corridor, the Southwest Corridor planners knit together neighborhoods that had been physically separated for more than a century. Not every resident viewed this as social progress…The existing railroad right-of-way created a dividing line between the South End and St. Botolph neighborhoods. Though these two areas held only slightly different economic profiles, their racial and ethnic compositions could not have been more different. St. Botolph residents constituted a largely homogeneous block of white families and some professionals working in the city. Though they themselves were city dwellers, many St. Botolph residents looked askance at the idea that deck cover would allow other urban neighbors easy access to parts of their neighborhood previously blocked by the railroad. These residents used the Corridor’s public meetings to voice their opposition. (p. 187)

In other words, the residents of St. Botolph engaged in fairly standard-issue urban racism, classism, and (one would imagine, given the increasing gay population of the South End at the time) not a small amount of homophobia–and saw in the democratic Southwest Corridor planning process an opportunity to (very democratically!) write their oppressive agenda in concrete. Unfortunately, Crockett’s handling of this rather obvious challenge to the viability of democratic planning is less than inspiring.

By listening and respecting the concerns of residents, [Southwest Corridor planners] were able to identify an architectural strategy that was responsive to the demands of St. Botolph’s residents but did not subvert the overall public planning agenda for the Corridor…[they developed] designs for a removable fence that could be unbolted at a later date should the neighborhood change its mind. Unfortunately, the design was compromised by another decision to lay granite at the base of the fencing, and when St. Botolph’s residents did, in fact, reverse their decision and requested direct access to the Corridor Park, it was no longer possible. (p. 188)

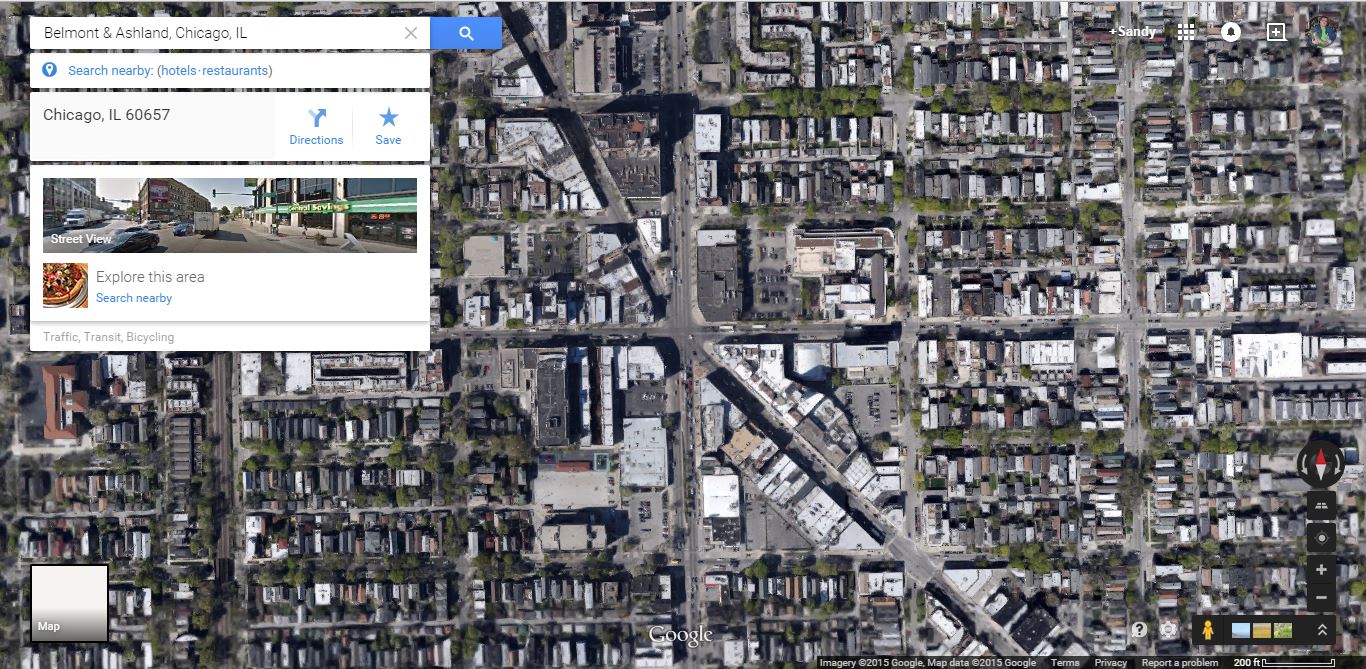

One must, I suppose, applaud the Corridor planners for their commitment to democracy, inasmuch as they were committed to listening to, to the point of acting to some extent on, an obviously bigoted agenda. To this day, many streets on the western side of the Southwest Corridor in this area dead-end at the Corridor Park with a wall or fence of some considerable height rising to prevent what should be an obvious pedestrian connection.

A democratically erected barrier preventing easy pedestrian access to the Southwest Corridor Park, Blackwood Street, Boston.

Crockett calls this “The seeming contradiction of a connective landscape needing to reconcile itself with existing race and class divisions and residents’ divergent opinions about what to do about them,” (p. 188) but–especially as one of the direct inheritors of the conflict around transportation planning in Boston–this feels like an unsatisfying resolution to me. Many of Crockett’s interviewees for the book talk about how they saw themselves as “advocacy planners,” adherents of a mid-’60s theory that planners should not be impartial experts, but advocates for the oppressed in society. It seems to me that there’s an obvious tension between this identification and engaging in a planning process that encodes racial and class injustice (literally building fences!) in the built environment in the name of “democracy.” While incredibly valuable for its documentation of the Boston anti-highway movement, and its repetition of the lesson that megalomaniacal centralized planning is generally abusive, People Before Highways would be more useful and convincing if it grappled honestly and openly with some of the shortcomings of the democratic, grassroots visions of planning that it advocates.

Akum Norder’s book, too, offers a lesson on this topic–and perhaps the juxtaposition of the two narratives can allow us to draw some conclusions about the intellectual and social milieu of participatory planning and its challenges. Norder’s book is an ode to her Pine Hills neighborhood, an absolutely lovely streetcar suburb-era area that reminds me strongly of the Westville section of New Haven where I grew up. Pine Hills originally and today is a strongly middle-class area with a strong communal identity; but it’s had its ups and downs, borders the “student ghetto,” and generally has some reasonable fear of tipping into neighborhood decline in the same way that most middle-class areas in cities that aren’t part of the overheated coastal housing markets do. As such (and seeing that many of the residents are educated, have money, or both), these neighborhoods are ripe for democratic, grassroots organizing around the issue of perceived problems–and using a democratic planning process to deal with them in a way that may work well for the neighborhood but not always for those pushed out as a result.

Norder profiles one such case (though without the slightly negative valence I’m attaching to it). She writes, on pages 204-205, of a property on the corner of North Allen and Lancaster that, at 5,921 square feet, held by the early 2000s twenty-six units. That is, of course, far more than current zoning would allow, but most of the neighborhood is nonconforming and grandfathered anyhow. Normally, such properties can continue unmolested unless the owner requests a change of use or makes major modifications; but city code allows for the property to be forced into conformance if it’s declared a nuisance property. And since the building in question does appear to have genuinely been a nuisance property, generating fights, noise, and an astonishing number of police calls, the local neighborhood association took the opportunity to force a zoning board hearing. They won, and the landlord had to empty the building to cut its units down to the allowed two.

So, on the one hand, this is a victory for a democratic planning process and for community concerns. The area residents took on a nuisance landlord, used the objective rule of law, and made their neighborhood a better place. Bully for them–we should encourage everyone to care about their neighborhoods like that. On the other hand, we’re talking about a process–a very democratic process–that led directly to the eviction of at least twenty-four people, with those who provoked it presumably taking no financial responsibility for their relocation. This being Albany, where rents are generally cheap, I think it’s reasonable to assume that few of those people were displaced from the area entirely; most were probably able to find housing relatively close, and quite possibly at not much increased rent. So the result isn’t necessarily the worst. But what if it weren’t Albany? What if this were a property in Boston, where rents are triple or quadruple what they are in Albany? Would we tolerate a neighborhood group getting together to democratically destroy what’s effectively an SRO, a vanishing resource for the very poor? How should a progressive advocacy planner react to this scenario?

I don’t have a coherent set of answers to these questions yet. But I think they’re crucially important to ask. And I think it’s important to recognize that the historical and socioeconomic context in which calls for grassroots, democratic planning came around has in many cases vanished. The type of democratic planning Kaitlyn Crockett profiles so well was a product of a city under siege, under threat of imminent literal physical destruction. Places like Albany may well still feel a lessened version of that threat. But in Boston, today, it’s gone. There is still a threat of displacement and destructive change, but it comes from the opposite end of the spectrum, from a hyperactive real estate market and the desire of many more people than the city has been willing to build housing for wanting to live here. Already in the time period that Crockett narrates privileged voices were figuring out how to use the democratic planning process to subvert planning aims of social justice and integration. We can’t, and we won’t, throw out the baby of democratic planning and extensive public outreach with the bathwater of urban renewal and highway building. But we can, and must, recognize that there are tensions between promising all comers a democratic process and achieving egalitarian, democratic outcomes. Just this past week the Globe wrote about how Boston’s input-based sidewalk-repair system is failing poorer neighborhoods that are less likely to call in for repairs. Is it possible, one must ask, that planners again need to start putting our thumbs on the scales of justice–this time, to tip them back toward the right?

Featured image source: https://www.jphs.org/transportation/people-before-highways.html