The question of whether public transit could be made free to ride has been gaining some considerable amount of media attention recently, driven in part by well-publicized (but uncertain) flirations in Paris and Germany. It is, of course, a sexy question, but one with very little track record and whose practicality is very much in question. There’s a reason that supporters of free transit point to the same few examples over and over again; there just aren’t that many cities that have experimented with fare-free transit. Even Communist countries have typically charged fares! But it’s a question that, quite reasonably in an age of increasing inequality, keeps coming up, whether from transportation writers in Chicago; lefty publications like Alternet (an article that, amusingly, comes to the standard bougie liberal conclusion that “people are just going to continue to drive, because they like it”); or extensively in the digital pages of Citylab.

Normally I’m kind of a killjoy on idealistic, speculative things like free transit. But I’m here to say that it’s something I’d actually like to see explored more–in very specific, limited circumstances. In an American context, someplace like Chicago–where tickets provide a significant chunk of the transit agency’s overall revenue picture–probably isn’t the place to start with free transit. By contrast, there are dozens if not hundreds of much smaller transit agencies in this country where farebox recovery (basically, and acknowledging that not every agency defines it the same way, the technical term for the percentage of overall operating expenses covered by ticket sales) is beyond low and in the “pathetic” (though understandably so) range. And I‘m interested in the topic of small-city transit. Luckily, Citylab has, in Eric Jaffe’s 2013 look at Chapel Hill Transit in North Carolina, already provided the beginnings of a blueprint for a situation where free transit might work:

The agency considered shifting to a fare-free system back in 2001 after recognizing that its farebox recovery rate was quite low — in the neighborhood of 10 percent. Most of its revenue was already coming from the University of North Carolina, in Chapel Hill, in the form of pre-paid passes and fares for employees and students. To go fare-free, the agency just needed a commitment from a few partners to make up that farebox difference. The university agreed to contribute a bit more, as did the taxpayers of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, and the idea became a reality…The original decision to go fare-free was part of a larger push by the community toward a transit-oriented lifestyle. In addition to eliminating bus fares, Chapel Hill Transit decided to expand service by about 20 percent. Meanwhile the university reduced parking on campus, Chapel Hill adjusted parking requirements in the downtown area, and the entire community made a push for denser development in the transit corridors. The ridership growth since 2002 can be seen as the result of all these efforts combined, says Litchfield.

To boil it down, the Chapel Hill experience seems to consist of the following factors:

- A low farebox recovery rate

- A strong institutional partner or partners to provide a built-in ridership base

- Increasing service to build ridership

- Political will to push transit-friendly land use and parking policies

- Dedicated funding to cover deficits

I’d add a few items of my own:

- Strong heritage land use patterns that are conducive to transit use, such as one or two strong transit corridors

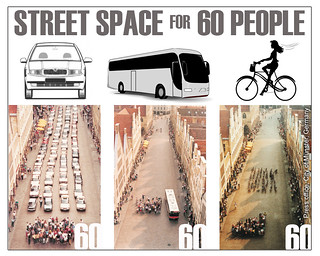

- Must be large or strung-out (think river towns) enough that transit, rather than biking and walking, is the appropriate sustainable mode

- A high percentage of workers both live and work locally

Aside from the first item, that’s a fairly foreboding list in most of the US. But it’s not an impossible one! It’s just not likely to be one that’s found in major cities. Rather, we might more profitably (heh) seek the future of experimentation with free transit in the smaller towns whose problems sometimes mimic those of big cities.

Let’s take a crack at identifying a few candidates. Given the criteria I’ve laid out–and my own geographic biases–my candidates will cluster in the Northeast US. I invite others to contribute other candidates!

Brattleboro, VT

Population: 11,765

Operating Agency: Southeast Vermont Transit (formerly Connecticut River Transit and Deerfield Valley Transit)

2016 NTD-reported fixed-route farebox recovery (fare revenue/operating expenses): 7.7% (note: reported number includes entire former Connecticut River Transit service area)

Percentage of town workers employed within town (2015 LODES): 52.7%

Brattleboro, via Bing Maps

Brattleboro’s a cute little town that’s a significant tourist and out-of-towner draw thanks to its hippie reputation, antiquing, its quaint and intact downtown, and the Brattleboro Retreat. The same intact downtown offers relatively limited parking and can get congested at busy times.

Brattleboro downtown parking lots, via the town’s website. Hey, that’s not actually so many!

Most of the town’s major employment centers are either downtown or centered on one of 3-4 major arterials, an ideal situation for serving them with transit–and, by small city standards, a quite high percentage of Brattleboro workers also work in town. Residential development is a little more spread out but mostly centered on linear corridors as well. Service radiates from the downtown transit center serving communities up and down the Connecticut River Valley and also across the mountains to Wilmington and (with a transfer) to Bennington, albeit not with any great frequency. Amtrak’s Vermonter stops very near downtown once a day in each direction. Given the current atrocious rate of farebox recovery and the town’s liberal politics, it’s at least mildly plausible to imagine a future in which Brattleboro decides to make a major push on bringing people downtown by transit and fills in its remaining downtown parking lots to help pay for it (and provide a push).

Sandusky, OH (h/t Bryan Rodda)

Population: 25,793

Operating Agency: City of Sandusky

Farebox recovery: unclear (not reported to NTD but it seems to lose a lot of money)

Percentage of town workers employed within town (2015 LODES): 26.1%

Sandusky, via Bing Maps

Sandusky is a touristy town on Lake Erie, home to the Cedar Point amusement park and a variety of other attractions. The downtown is somewhat disinvested but hasn’t been totally wiped out by urban renewal. Commercial development clusters along major corridors, but the percentage of locals who have managed to find work in town is, according to LODES, fairly low (though not terrible by the standards of a city this size). There seems to be a lot of room to grow–and perhaps free transit would be the way to make that happen.

Rutland, VT (h/t @peatonx)

Population: 16,495

Operating Agency: Marble Valley Regional Transit District

Farebox Recovery (NTD 2016): 3.8%

Percentage of town workers employed within town (2015 LODES): 45.4%

Rutland, via Bing Maps

Hometown of Boston-area urbanist journalist Matt Robare (support his Patreon!), Rutland is a down-on-its luck former quarrying town with some proximity to ski resorts. It’s a reasonably dense town with a few obvious transit corridors and some decent job concentrations, and a fairly high proportion of local workers work in town, while others surely would happily ride transit to ski resorts such as Killington. There’s room for infill, too, such as the giant strip mall that sits on top of the former railroad yards; but residential growth is anemic and locals have rejected plans to bring refugees to the area. Rutland is struggling economically, though, and lacks the kind of major anchor institutions that could typically provide funding, so despite the local transit system’s terrible farebox recovery finding more funds to make transit free may be a no-go.

Michigan City, IN

Population: 31,479

Operating Agency: Michigan City Transit

Farebox Recovery (NTD 2016): 7.8%

Percentage of town workers employed within town (2015 LODES): 38.7%

Michigan City, via Bing Maps

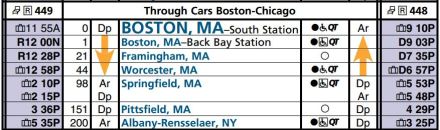

A sometime muse of mine, Michigan City is an interesting place because by the standards of small Midwestern cities it’s quite transit-rich, offering both Amtrak and South Shore Line rail service to Chicago, even if the two operators don’t cooperate quite as much as they should. It is, otherwise, a quasi-Rust Belt town that has struggled to reinvent itself; urban renewal and a casino have, predictably, not yielded much in the way of results. Aside from good rail service, it has the transit advantage of having one very strong, identifiable north-south transit corridor along Franklin Street around which much of the city’s employment clusters and that connects to both the South Shore and Amtrak. Land use in that corridor is far from ideal, and residential demand is mediocre, but this is a classical “good bones” case.

Conclusions

I’ve offered, I think, a few plausible real-life cases where free transit could work. But the case studies here also demonstrate the difficulty of making such a dream reality. Some of these towns would almost certainly lack the ability to raise sufficient funds locally to make transit free; it’s hard to imagine, say, Rutland or Michigan City finding the money. You can’t tax the wealthy or major corporations to make transit work when capital–not to mention major corporations–has already abandoned your city. And local funding streams, even when feasible, are notoriously fickle; even Chapel Hill Transit has had to consider charging fares at at least one point. To make free fares work while also increasing service to the point where it could make a real difference in the life of the city would probably require a substantial, long-term commitment from a higher level of government, but I would be very interested in seeing a wealthy state or the federal government take this on as an experiment. The money pouring in, of course, would have to be matched by local measures on land use, parking, and planning, which makes the entire exercise fraught. But it’s not hard to envision something potentially working. It’s certainly worth more experimentation.